“Give me all that thine is

and I will give you all that mine is.”

God to Mechthild of

Magdeburg

The Divine Exchange

How do we access the insight, resilience, and unbroken love of our divine essence—the spiritual heart? Many spiritual explorers practice complex techniques, but others take an uncomplicated path: They simply offer themselves to God, the way beloveds give themselves to their beloved. At the same time, they open themselves, becoming receptive, so that God may impart divine grace to them.

The process of offering oneself to the sacred has been called, “consent,” “surrender,” “self-giving,” “releasing,” “self-emptying,” and so on. The relationship with the divine that emerges through surrender is mutual and reciprocal, revealing a bond that is everyone’s birthright.

For centuries, spiritual traditions have described this sacred exchange—this sharing of gifts between human and divine. In the New Testament, for example, the author of the book of James advised, “Draw near to God and he will draw near to you.” In medieval Germany, Christian mystic, Mechthild of Magdeburg, explained that prayer “drives the hungry soul up into the fullness of God, and draws the great God down into the little soul.”

In the Hadith Qudsi, God described the divine exchange to Muhammad saying, “My servant draws near to me with ceaseless devotion until I love him. And when I love him, I am the hearing with which he hears, the sight with which he sees…, the foot he walks on.”

Najmoddin Kubra, a thirteenth-century Sufi from Central Asia, portrayed the meeting of the divine light and the light that lives in the human heart. He said: Whenever a light ascends from a wayfarer, the divine light descends toward that person. Early on the spiritual journey, human and divine lights meet mid-way, but when the human light is strong enough, the divine light yearns for the seeker. Like attracting like is the “secret of mysticism,” Kubra explained.

In ancient India, bhakti yoga (the way of devotion) derived its name from the root “bhag” meaning, “to share.” Followers of the bhakti path believe that God promises to impart divine consciousness to them to the extent that they sincerely offer themselves to God.

In twentieth century India, the sage, Ramana Maharshi, wrote a poem to the divine entitled, “The Marital Garland of Letters.” In the last lines, he asked his “Living Lord” to bring about this exchange, symbolized by the sharing of two garlands. To God, he implored: “Place your garland on my shoulders and with this my garland on your own.”

Mad Bear, a contemporary Native American teacher, explained how to connect with the sacred. There must be relationship and offering, he said. Give to the Mother, instead of taking. Always there is consent and exchange, both jointly given.

When we practice the Art of Surrender, we use the expressive arts to give to—and receive from—our divine nature, the God within. Through creative expression, we gather the various parts of our ordinary selves, as if they are flowers in a field, as if each bloom is a gift for the spiritual heart. Having offered this bouquet to the beloved, we wait, open and expectation-free, to receive from our sacred core.

Surrendering Through Art

The Art of Surrender is a simple three-step spiritual practice. During this process, we create symbols for our ordinary self and our divine nature, then we allow these two to join in a Communion Symbol. Although the Ordinary Self Symbol is often created first, these steps may be explored in any order.

Step One: Ordinary Self Symbol

We begin the Art of Surrender by pausing to remember our divine nature, and our desire to realize our identity with this essential self. Having recalled our sacred purpose, we then wonder, “Who am I as a human person—right now, in this very moment?”

Because the Art of Surrender is a meditation-in-action, the answer to this question is not “thought up.” Instead, we quiet our mind, and turn within. Then, we explore our inner world through feeling—through wordless self-sensing. Waiting in mental stillness, we may notice a body sensation, image, inner sound or scent—or the desire to assume a certain physical pose. Sometimes we hear pithy word-phrases— communications from below the conscious mind. Whatever arises, we practice receiving this part of ourselves without becoming attached to it. Then, we give outer form to what we’re experiencing, using art media.

As we create, we stay close to our felt silence. If judging, strategizing, or striving thoughts arise, we either make them part of our self-inquiry—or we acknowledge them, and let them go.

Step Two: Divine Nature Symbol

With step two, we again let curiosity draw us inward, this time wondering, “Who am I today as a spark, a current, a breath of the divine? Which aspect of my divine nature do I glimpse right now, in this very moment?”

As with step one, there is no need to “figure things out.” Instead, we allow the answer to come through felt, silent waiting—which means “not knowing” for a while.

Once we’ve seen, heard, felt, or touched something of our divine nature, we portray what we’ve experienced through movements, sounds, and/or art supplies. Sometimes during this step, gratitude for this revelation arises spontaneously within us.

In our groups, direct access to the divine varies from person to person. Some expressive artists work with the symbols of their religious traditions. Others have subtle, fleeting glimpses of their divine nature. Still others, intimate with their inmost being, portray aspects of their core self fluidly and with ease. Wherever individuals are on their spiritual journey, all movements toward—and experiences of—the divine are welcomed.

Step Three: Communion Symbol

We begin step three by wondering, “Who am I, right now, as a whole person—as someone in whom the human and divine qualities that I’ve just portrayed are joined?”

The answer to this question comes through silent, felt waiting, too. When the answer presents itself, we portray it with whatever artistic media beckon. We may place our Ordinary Self and Divine Nature Symbols side-by-side, for example, or we may place one atop the other. Sometimes, a third, new artpiece emerges.

If we feel as these two depictions come together—rather than joining them mechanically—spiritual transformation becomes possible. If, at the same time, we consent to being changed by God, then something inside us can shift—softening, opening, clarifying, releasing. For some expressive artists, the “joining” that occurs during the creation of a Communion Symbol means allowing two opposites to come together. For others, “joining” means recognizing that the union of human and divine within us has been present all along.

Please be mindful:

When we turn within, wanting to deepen our self-awareness, whatever is hiding within us rises to the surface, so it can be acknowledged and released. Sometimes this includes unsettling memories.

If you have a history of serious mental or emotional distress, or a history of trauma, I hope you will explore this practice in the company of a psychotherapist, minister, or wise friend. Someone anchored in his or her divine essence must be present during these creative self-inquiries, so that distress does not overwhelm you. If you are deeply grounded in your own divine core, this “someone” could be you.

Art of Surrender groups, and one-to-one mentoring sessions offer safe, supportive ways to explore this spiritual path.

Mystical Marriage

According to transpersonal philosopher, Michael Washburn, when the joining of the human and the divine self becomes evident, the seeker enters the “integration” phase of the spiritual quest. During this culminating stage, the ego (the personal self) aligns with the divine self—the “dynamic Ground” (to borrow a term from Washburn’s book, The Ego and the Dynamic Ground).

The energies of the Ground, which have been blocked, now begin to flow freely through the body. Spirit and body start working together: The body becomes spirit-filled, and spirit becomes embodied. At the same time, thought and emotion, which once seemed opposed, reconcile, allowing emotion to be guided by reason, and thought to be informed by felt experience.

Over the centuries, mystics have often used poetic, metaphorical language to describe the joining of their ordinary self with the indwelling God. This merging, they say, is like a courtship that leads to a spiritual marriage. Wanting to express the intensity, immediacy, and intimacy of their experiences of God, they call upon romantic similes and metaphors.

In lectures given in 1997 in Colorado, Cistercian monk, Thomas Keating, portrayed the spiritual journey as a “divine romance.” According to Fr. Keating, this romance, like human ones, usually begins with conversations—talking to God, and listening to God’s Word. In time, words fall away, and seekers attune to God’s wordless presence. Then, conversations unfold in silence—being-to-being. Now called to divine union, individuals sense that God’s nearness resembles an embrace, a kiss, an intermingling. At first, these experiences of pure love are brief, but as the body learns to allow this exquisite intimacy, union becomes an enduring state that remains during daily life.

In this portrayal, Fr. Keating drew upon the ancient Judeo-Christian tradition of “spousal” mysticism, in which God and mystic are “betrothed.” In the biblical book, the Song of Songs, for example, the spiritual seeker passionately beckons to his divine beloved, saying

Rise up, my love, my fair one,

and come away.

For, lo, the winter is past,

and rain is over and gone.

The flowers appear on the earth;

the time of the singing of birds is come….

Arise, my love, my fair one,

and come away.

(Chapter 2:10-13, KJV)

Centuries later, in The Interior Castle, St. Teresa of Avila described the “spiritual marriage” that emerges when the individual soul rests in its core with the divine. This love-union, she explained, is like showers descending from on high into a stream. These two liquids become one water that can never be separated.

Romantic language is not unique to the Judeo-Christian tradition. At the age of thirty-five, twentieth-century Hindu sage, Ramana Maharshi, wrote, “The Marital Garland of Letters.” In this long poem, he addressed the “All-embracing Light,” his “Living Lord,” saying:

The moment I thought of your name,

you caught and drew me to yourself.

(Verse 70)

Out of my house you enticed me,

into the chamber of my heart you entered.

(Verse 97)

[Through your grace] you…held me tight

and consumed me.

(Verse 103)

As snow in water melts, let me dissolve as love

in you who is all love.

(Verse 101)

Wed me…so that [my mind] may be

fragrant with infinitude.

(Verse 69)

The Sufis, the mystics of Islam, are also known for their love poems, written to the divine beloved. While in the mystical state of union, al-Hallaj, a 9th- and 10th-century mystic from Baghdad, exclaimed:

I have become the One I love, and the One I love has

become me!

We are two spirits infused in a (single) body,

And to see me is to see Him,

And to see Him is to see us.

The famous Sufi poet, Rumi, who lived during the thirteenth century in present-day Turkey, counseled his students to embrace the mystical marriage. “Marry your own soul,” he advised. “The wedding is the way.”

Of course, human romances seldom unfold smoothly, and during the divine romance we humans often experience anxiety, fear, confusion, and doubt, too. The ease with which the divine “love affair” unfolds depends upon the extent to which our human attachments and aversions disrupt our ability to give to—and receive from—the divine.

When attachments (clinging thoughts and behaviors) and aversions (dislikes and avoidant behaviors) preoccupy our minds, they block awareness of the subtle promptings that emanate from the God within. Each time our ordinary self holds on (“I can’t release that, I need that to be happy!”), our selfgiving is restricted. When we think, “I expect God to give me what I want, when I want it,” this demand blocks our ability to receive unimaginable blessings.

When we repress knowledge of unwanted aspects of our personality, antipathy to this “shadow side” limits our self-giving (we can’t give what we don’t possess!). If we decide, “I won’t open to God, I might be given a task or talent I don’t like,” this aversion makes it hard to receive the liberating experiences we need.

Those who pass through the trials of the divine courtship cherish the resulting blessings. In sixteenthcentury Spain, in the poetic prologue to his “Dark Night,” St. John of the Cross described his marital delight:

On a dark night, kindled in love with yearnings—oh,

happy chance!—

I went forth without being observed, my house

being now at rest….

My face I reclined on the Beloved.

All ceased and I abandoned myself, leaving my

cares forgotten among the lilies.

When we engage in the Art of Surrender, we follow in the footsteps of the world’s mystics. Their courtships with the divine beloved bore fruit in the jungle caves of southern India, the stone built churches of western Europe, the roadside inns of Central Asia, and the mountain monasteries of rural America.

Our twentieth-first-century urban environments are different, of course. Practicing the Art of Surrender, we sit in temperature-controlled rooms, on soft chairs, with art supplies spread before us. But the same opportunity awaits us as awaited those who came before: To experience the divine romance—and its consummation—within the temples of our own bodies.*

*Please see the Credits page of this website for the resources used to write this essay.

Heart Gallery

Below are samples of Art of Surrender creations, selected to show the various forms that this kind of expressive art may take. Some are drawn, some are written, some are constructed with paper. Many use three art-pieces; others portray the three Art of Surrender images (Ordinary Self Symbol, Divine Nature Symbol, Communion Symbol) with only one or two depictions. Please note that each person chooses her or his own imagery and vocabulary when creating their three symbols.

I’m grateful to these expressive artists for sharing their introspective work with a wider audience. As you view their work, remember to sense their images—and your own inner world—while you think about what you’re seeing.

Please click on the artwork to see a larger version.

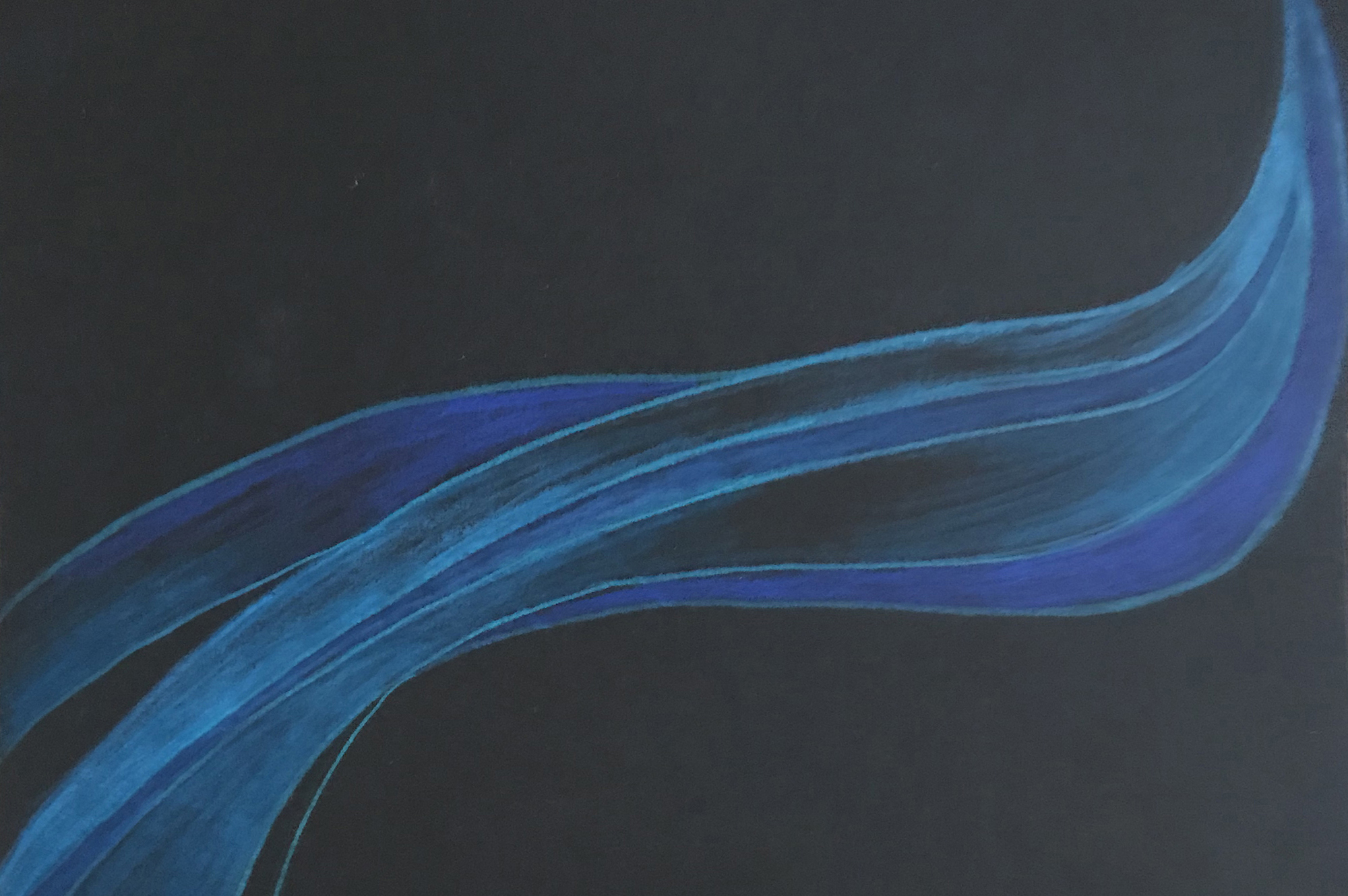

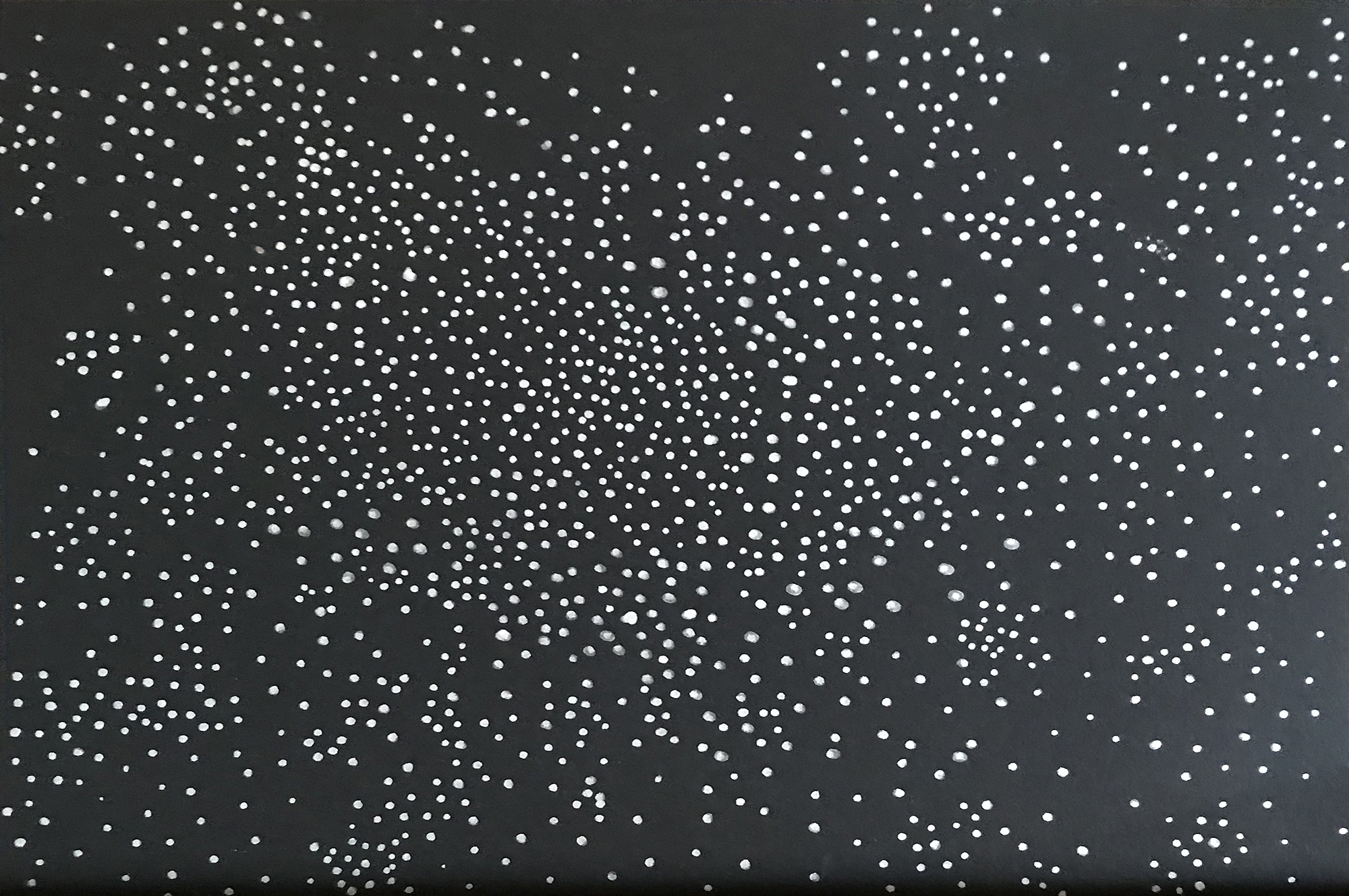

“Divine Silence takes Sorrow into Itself”

“I call this Ordinary Self picture, ‘The River of Sorrow.’ Its origins began when my father-in-law died. His death triggered memories of my own father’s death, my husband’s recent illness, and the deaths of two grandfathers. Holding all of these experiences at once, I was flooded with sorrow.

“When I took step two in the Art of Surrender process and opened to my core self, I entered the divine silence—a familiar experience. But how could I portray a stillness that is also vital? Then, in my mind’s eye, I saw specks of light on black. As I put this image on paper, I realized that where I worked inattentively, the picture looked diffuse and sloppy. I needed to be mindful as I drew, placing each light-dot with awareness.

“Finally, I invited the two images to join. I watched, through my inner eye, as the divine silence swirled, taking sorrow into itself. While I drew this image, I felt relief, remembering that I was contained by a reality—a compassionate power—that was larger than grief.”

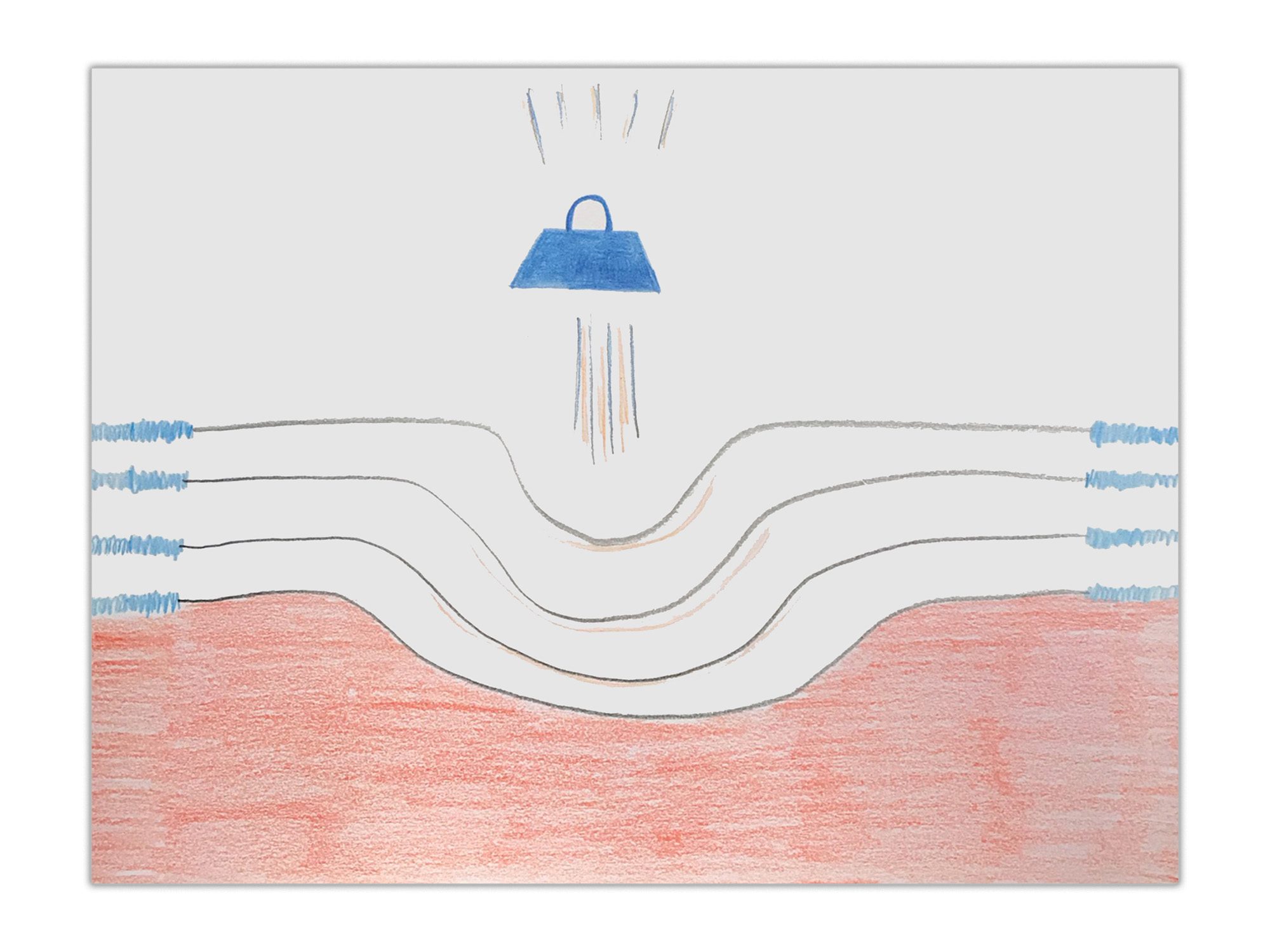

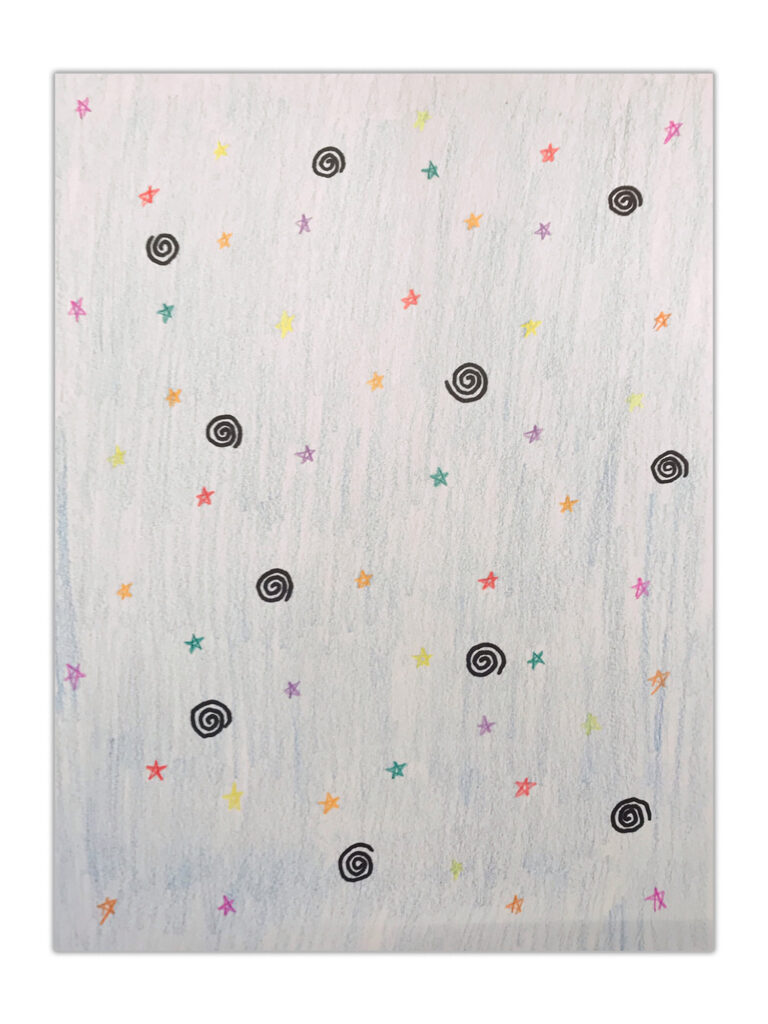

“Pressure Shrinks in the Big I”

“I began this workshop feeling pressure. I sensed a heavy weight pushing down on walls of inner tension, causing springs within me to coil. I symbolized the Little I’s interior life with the color red.

“When I looked for my Vast Self (the Big I), I discovered that it was blue and contained two figures: swirls representing big “Ah-ha’s,” and star shapes representing truth or knowledge.

“When I brought these two experiences together, I placed my Vast Self below the Little I. Then, I noticed the Little I’s walls breaking down, letting the weight enter the Vast Self. Next, this weight became smaller and less significant. As the Little I (in red) bled into spaciousness, layers of defense and resistance broke through, and I felt tension release.”

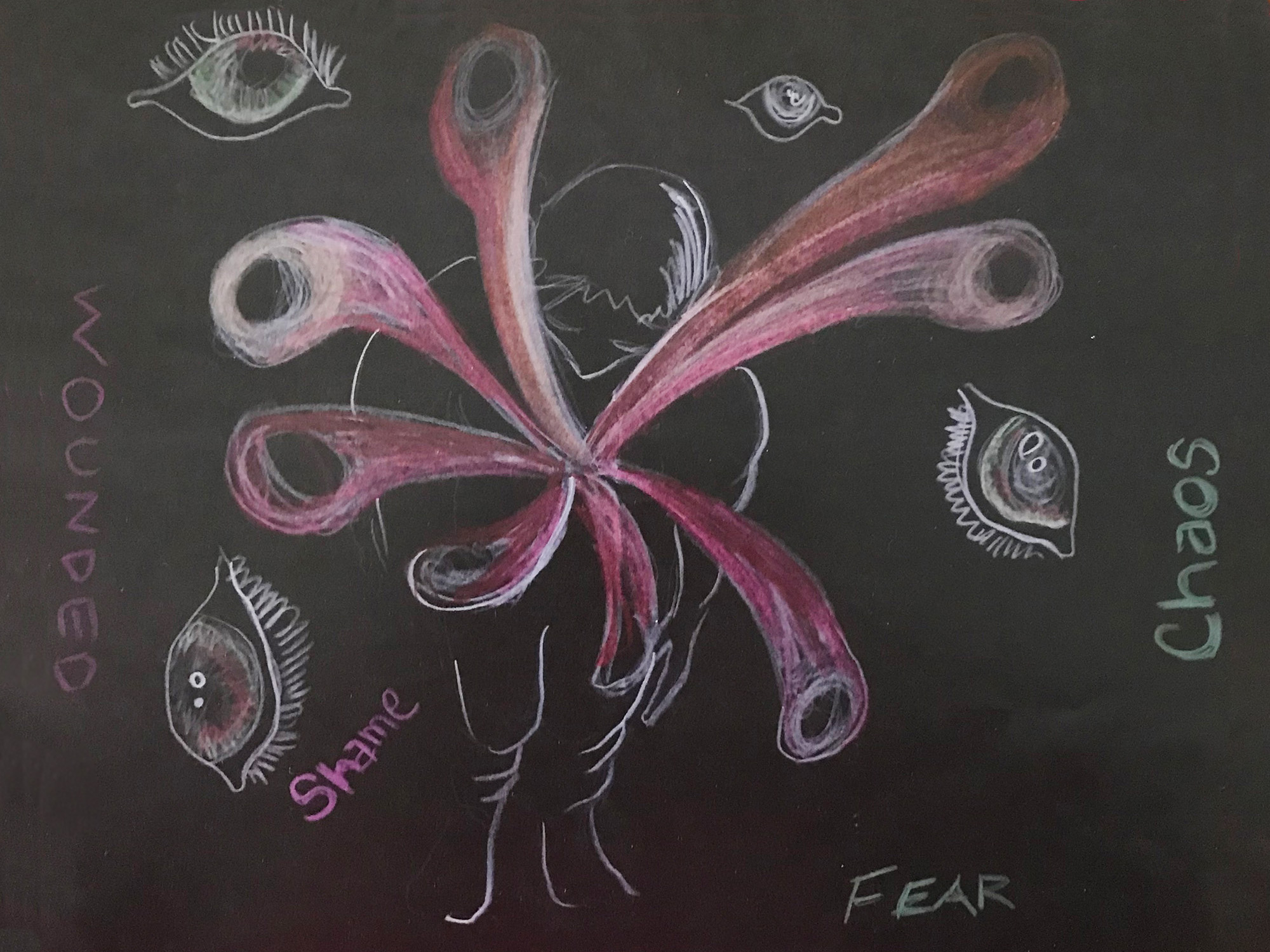

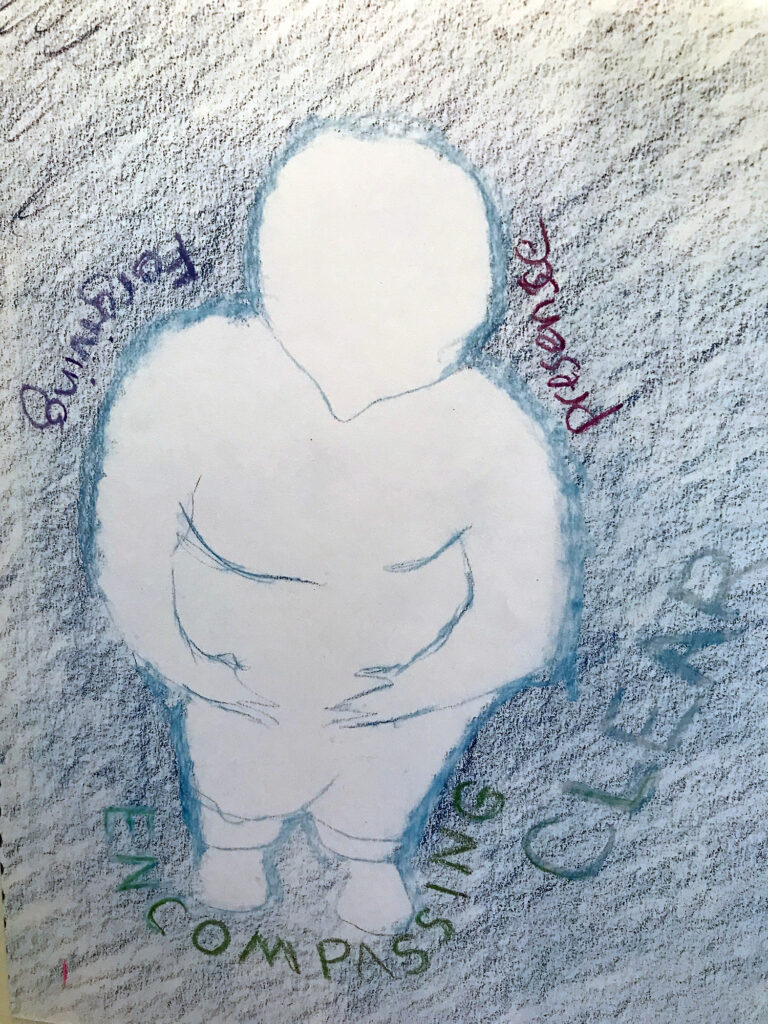

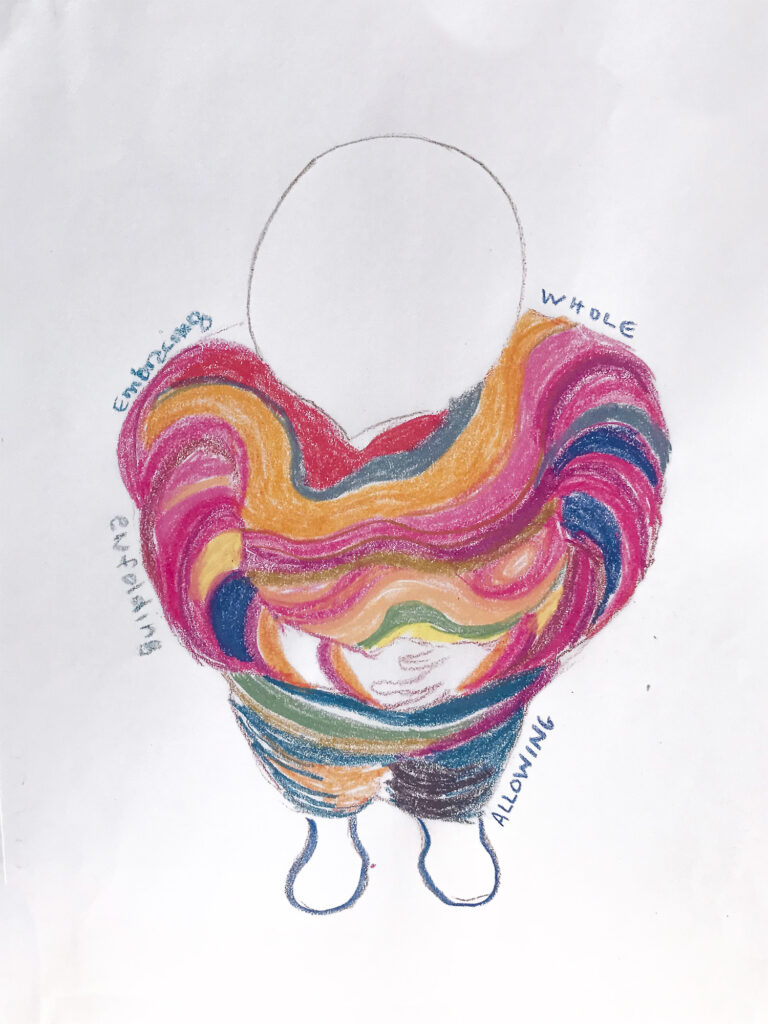

“From Chaos to Wholeness”

“Turning within, I recalled my childhood when critical eyes judged me, and adults trapped me in their rules. Overwhelmed by chaos, fear, and shame, I was ripped apart by life.

“For my next step, I shifted into my Clear Self, feeling present, forgiving—and something encompassing.

“When I thought about bringing these two images together, integrating them seemed impossible. But then, I realized that the Art of Surrender is like a Buddhist koan [a paradox that can only be resolved by deep, wordless awareness]. Suddenly, I knew what to draw: I would allow the elements of my childhood chaos to turn into a healed and whole energy body. It was only after I’d completed this last picture that I realized I’d drawn my hands interlaced—integrated, that is.”

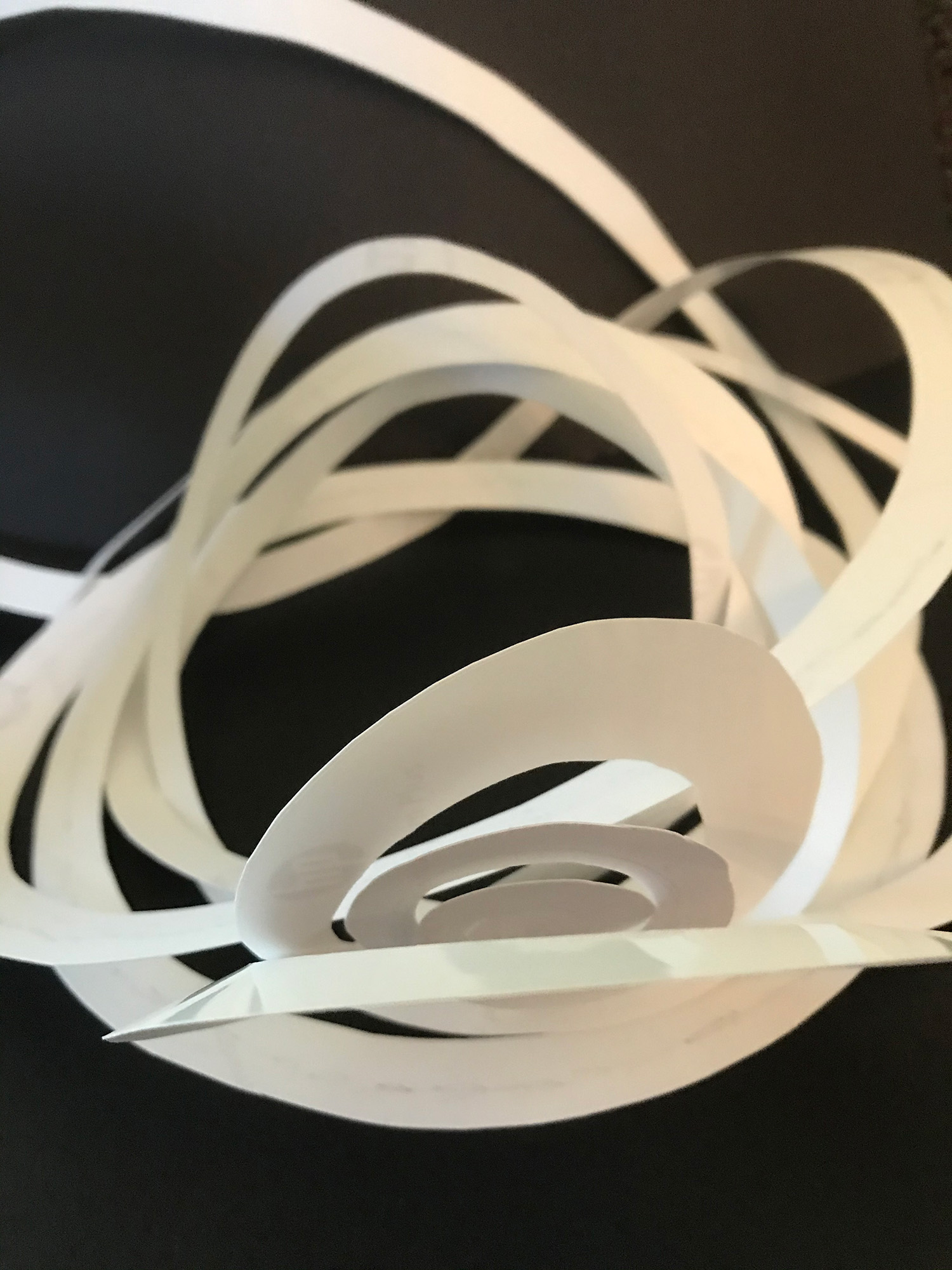

“Uncoiling in Liquid Light”

“One day while meditating, I experienced myself as a tight coil. I knew I was feeling stress (having too much to do in a small amount of time), but I had no idea how taut and tangled I was.

“I kept meditating, and soon I felt a gentle light inside me. At various times, it shimmered, pulsed or flowed. As I gave my attention to this subtle radiance, the tense inner coil relaxed, turning into a spiral. Then, an insight came: The wound-up coil and the spiral were the same shape—the only difference being that the spiral was a relaxed form of the coil. Soon after, I captured this experience through expressive art.

“I created my ‘coiled self’ by cutting a coil out of paper, then tangling it with itself. Next, I drew the ‘liquid light’ image on a separate piece of paper, holding a flashlight to illumine the drawing. To portray the wound-up me relaxing in the divine presence, I used scissors to narrow the coil, then placed it on the ‘liquid light’ picture. I named this Communion Symbol, ‘Unwound.’

“A couple of days later, anger flared inside me during a disagreement with my husband. I waited before responding and, during that pause, the ‘Unwound’ image appeared in my mind’s eye. Recalling it, my anger drained away, and I spoke calmly and clearly to my partner.”

“Resting in the Lap of God”

“After I quieted myself, I waited for a metaphor that would become a trailhead—a direction to explore. This time, the first image that appeared was a holy symbol; my ordinary self symbol came later.

“In my mind’s eye, I saw a soft, off-white ethereal color that felt alive and had substance. My body was warmed and embraced by it. When I was thirteen years old, I’d seen this same color in a dream. Then, as now, it symbolized divine Presence. Today, I sensed that this color was also embracing, like a lap. So, using fabric and sturdy cardboard, I created a receptive lap.

“Simultaneously, I was aware of distress in my life, which I often experience as a restrictive black ball located in my lower chest. The black outer shell of the ball is a protective buffer, hiding the richness of my authentic personality, which is concealed within. This impervious shell separates me from myself: it keeps what’s inside me from being seen or heard, and it keeps perceived external dangers out. I used tissue paper to portray this ball—both the black shell, and the layers of my colorful interior.

“When I brought the black ball to the divine lap, I knew I wanted to make my hidden inner layers visible. Cutting the black ball in half, I revealed my hurt and sorrow—and other raw, tender, vulnerable parts of myself. A more wholesome and vibrant ‘me’ was emerging. Placing the now-open black ball in the divine lap, I knew that my distress was being held by divine Presence. I didn’t expect this distress to magically disappear, but I knew that now painful emotions would be less likely to overwhelm me.

“Later, I placed my divine nature symbol (the divine lap) on my home altar. It feels holy to me. When I’m distressed, I often write my concern on a scrap of paper, then place it in the lap for divine holding.

“Long after I’d created these images and placed my divine nature symbol on my altar, I realized that the core of my open-ball is the same color as my divine lap.”

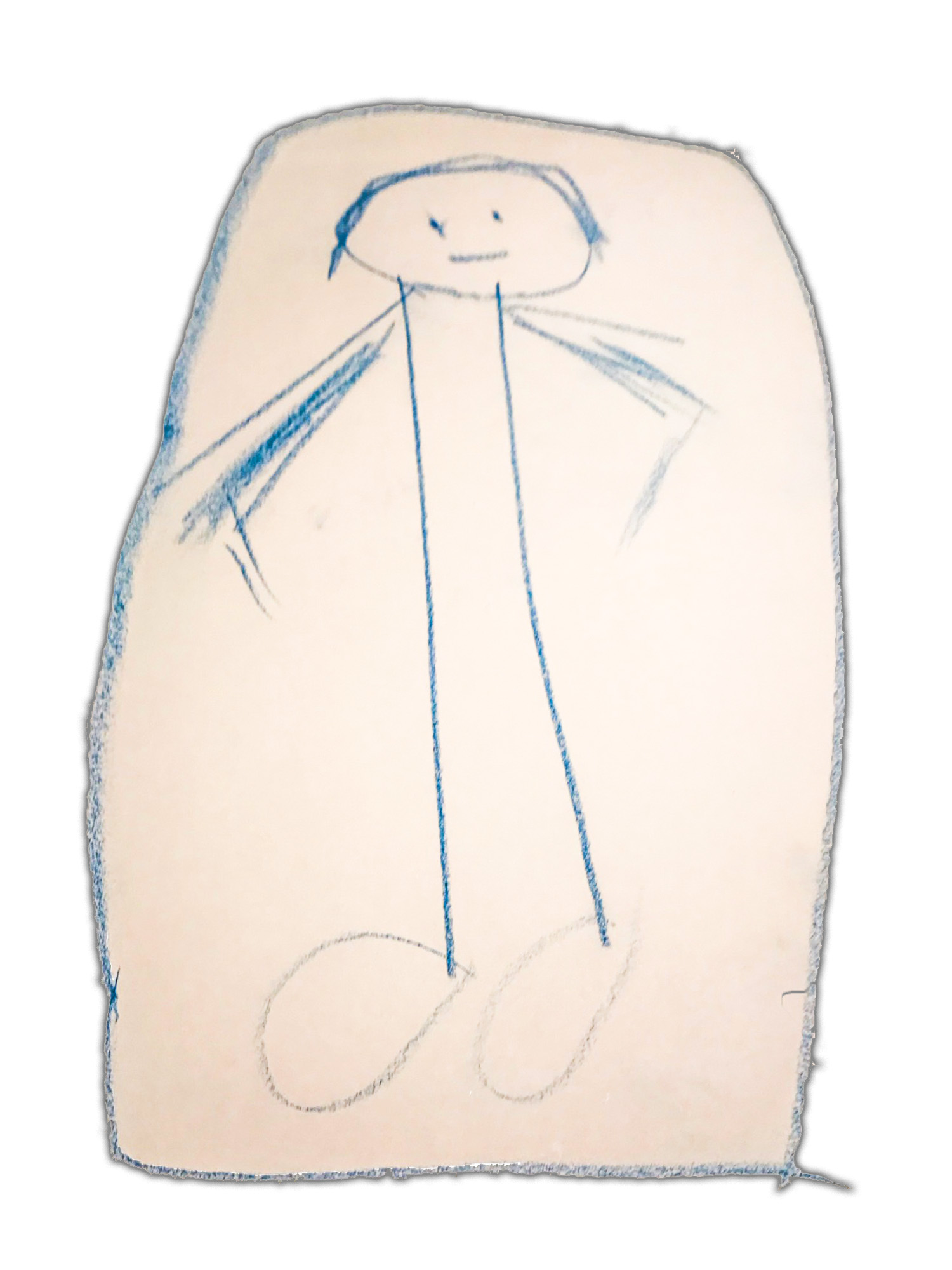

“Freeing the Narrow Self”

“Thinking of my ego as the ‘narrow self,” I drew myself as a straight body enclosed by a narrow box. The box was made by others, creating a joyless, restrictive existence. At the same time, my narrow, straight body implied focus, directness, and discipline, which I like.

“Next, I depicted my vast self as boundary-less. This self contained everything: tears, music, laughter, and many elements of nature. The human figure was not yet in the picture.

“I began my third creation by remembering that I’d had a dichotomy between my narrow self and my boundless self for a long time. As I placed the straight, direct me into the vast self picture, this dichotomy faded. Then, I was able to be the focused ‘me’ in many area of life. Some figures went off the page, beyond the boundary, showing only hands and feet. How fun! In this third picture, I’m contained in the physical world, but the container is neither rigid nor externally imposed. The container is love—life-giving to me and others.”

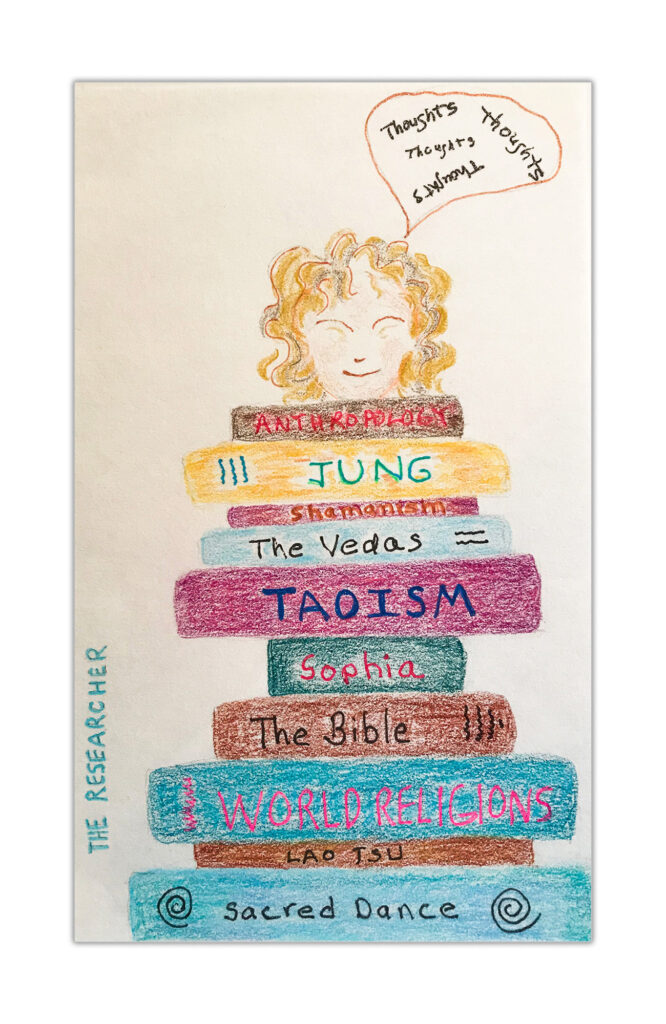

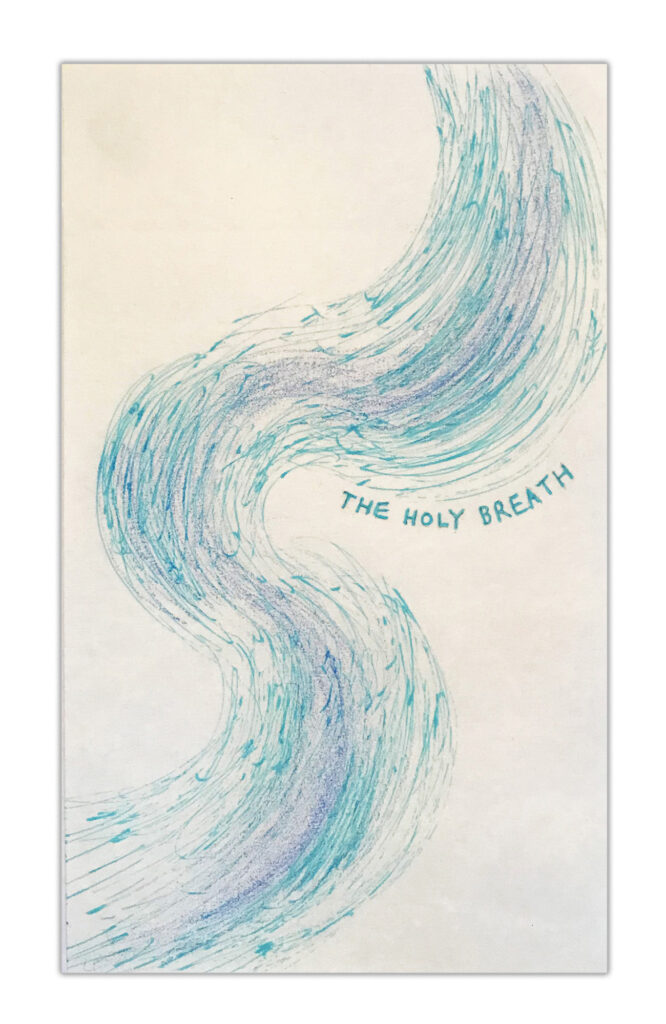

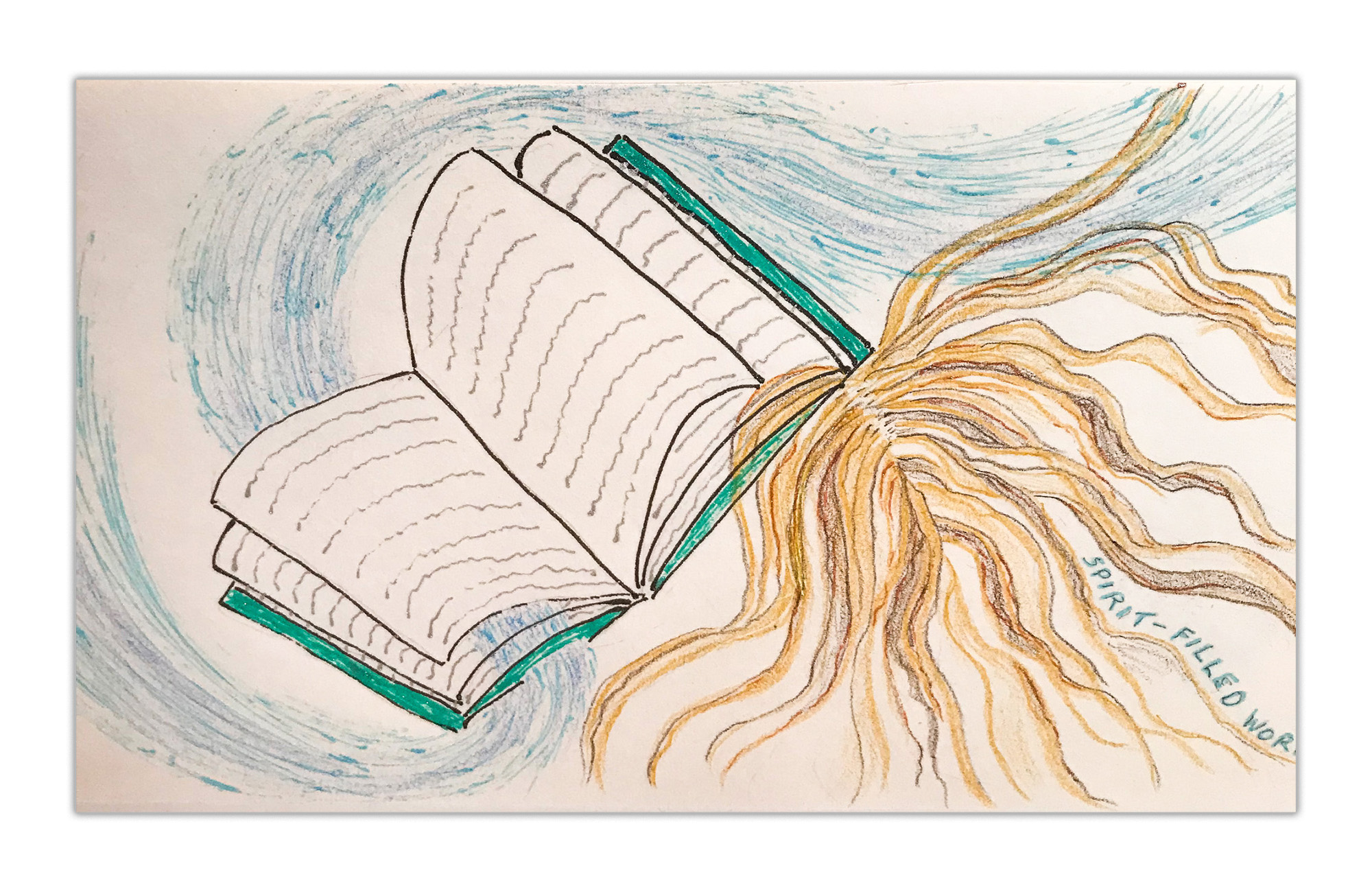

“The Holy Breath Infuses Work”

“I’m a researcher. I love to read and write in the field of comparative mysticism. I consider this passion to be a gift, but sometimes I become overly mental, forgetting to feel my divine core. This Ordinary Self drawing shows me as a happy researcher, preoccupied with thoughts.

“When I turned within, looking for my divine self, I noticed my breath flowing inside me, without conscious effort. Knowing that the breath flows from a Source vaster than the ordinary me, I drew the Holy Breath to represent my divine nature.

“When it was time to create a Communion Symbol, I was stumped. How could a pile of books and the divine breath ever join? I closed my eyes and waited, and kept waiting. Then, while resting in my interior quiet, I sensed wind blowing through my hair. Summoning my courage to create an image I didn’t believe I could portray, I drew my hair—and then the pages of a book—blowing in the Holy Wind. Through these images, I reminded myself that the divine is always here, able to enliven my everyday work.”

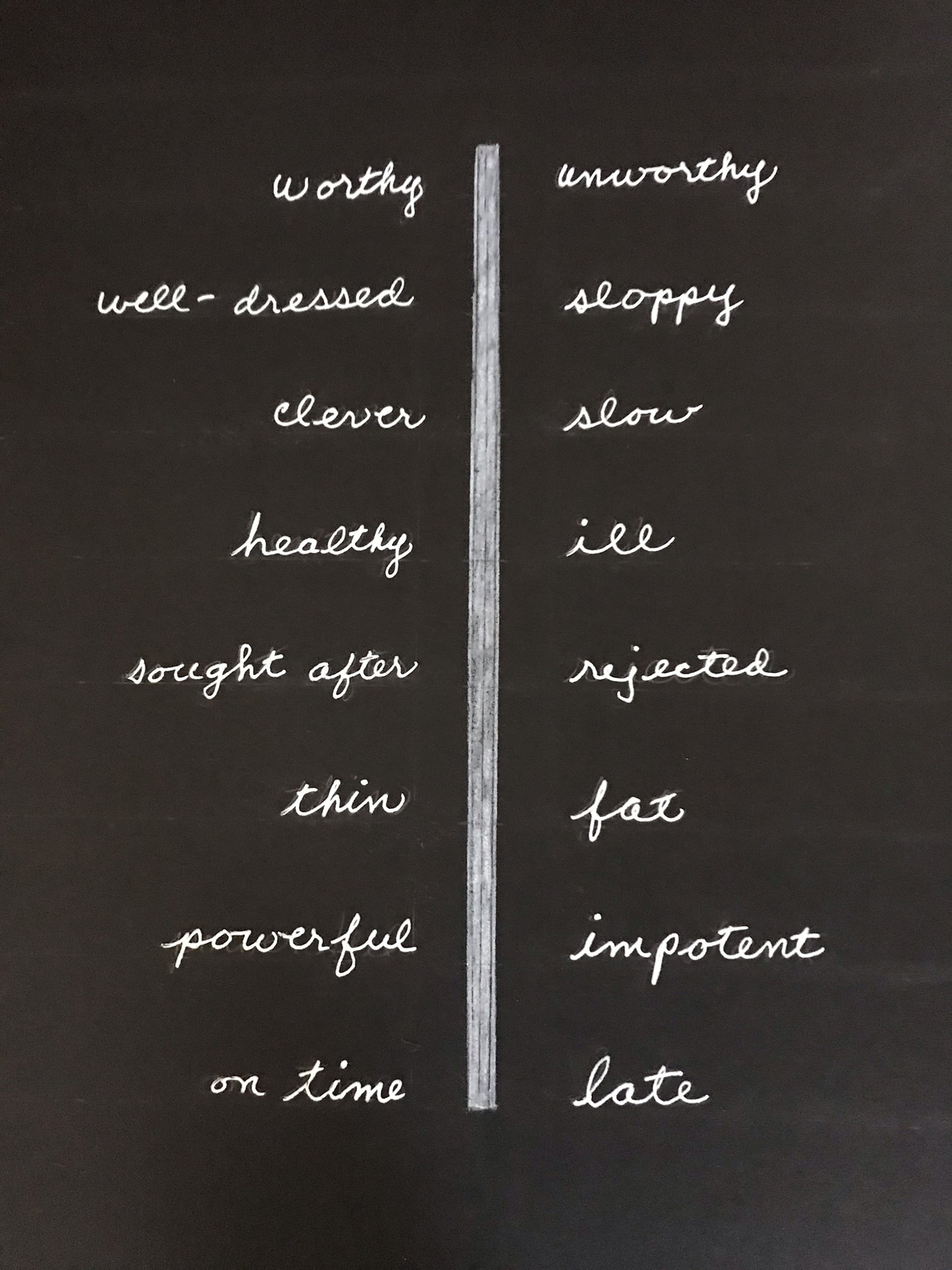

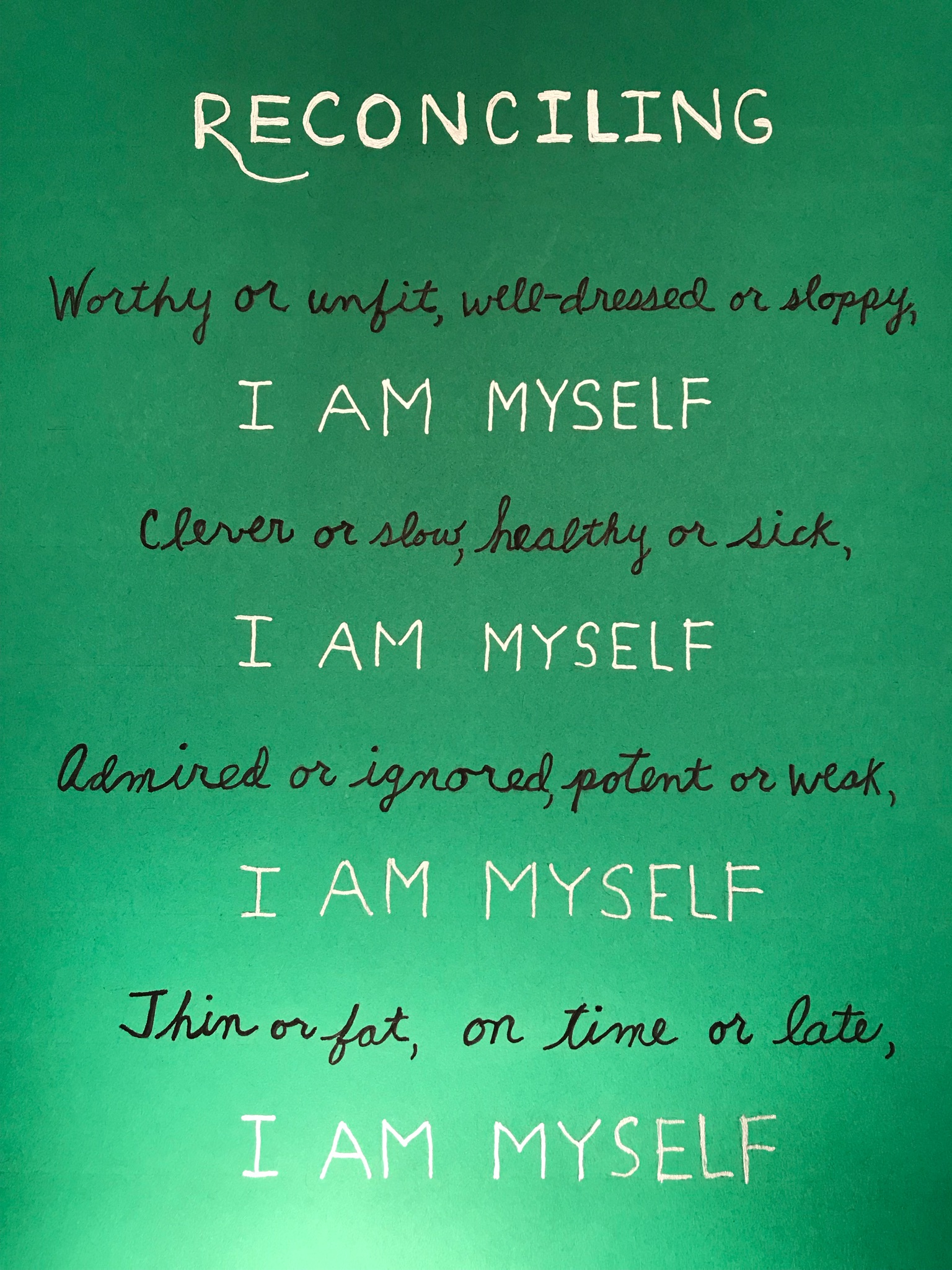

“Opposing Judgements Reconcile in Being”

“I decided to experiment with the Art of Surrender process, this time using words instead of images. Before the workshop, I’d been judging myself a lot, sometimes with negative ideas, sometimes with positive ones. I’d watched as my thoughts oscillated, back and forth, between criticism and praise. To depict my superficial, ego-self, I recorded this pendulum swing between opposing judgments.

“When I quieted my mind, looking for the vaster ‘me,’ these judgmental thoughts faded. I felt as though I were descending into a deep pool of being, which was both quiescent and alive. Resting there, I waited, hoping to see or hear something true. In the silence, I heard the phrase, “I am myself”—which I took to mean, “I am my Self.” Repeating these words, I felt centered, as if I’d touched a core, inmost self that was both deep and vast.

“When it was time to put the surface and the deep ‘me’ together, their joining was easy. I simply alternated my opposing, judgmental thoughts with the fathomless, sacred one. The result was a poem—a spontaneous prayer to remember, especially when I forget the whole of who I am.”