“Listen to the presences

inside poems, let them take you

where they will.”

Rumi

Poems as Portals

Poetry, by its very nature, creates portals—doorways into unexplored dimensions of ourselves. Poems seldom move logically from point to point. Instead, they communicate through omissions and spaces as much as through concepts. Removing unnecessary words and unneeded punctuation, poetry is essence-talk. This kind of writing occupies the threshold between concept-filled speech and contemplation. The spaces it creates invite us into silent, wordless experience.

Poems offer gateways into the body and its senses, too. Poets don’t usually talk about things; they incarnate what they describe. Seen through their eyes, waterfalls aren’t simply about the speed and volume of water flow, or the angle of descent. The waterfalls that poets describe immerse us in roaring sounds and pungent scents—in the caress of gentle mists, the taste of earthy wetness, the dance of light on translucent drops, the dizzying sense of free-fall. Inviting engagement with the body and its perceptions, poets alert us to a wisdom that lives below the thinking mind.

Poetry also draws us into cadence—into rhythms that are built-up by the intentional arrangement of stressed and unstressed syllables. The primal beats of the human heart and of tribal drums echo within poetry. When a poetic verse is emotionally charged, it may even call us into wild and unexplored parts of ourselves.

Poems can bewilder us, too. Often, they juxtapose ideas, objects, places, and actions that don’t normally belong together. Consider, for example, the rapidly changing images in the poem, “Wax,” written by the Sufi poet, Rumi (translated by Coleman Barks in The Essential Rumi). Rumi begins this poem by declaring himself crazy because he’s broken into his own residence, nabbing his own money. But then, without warning, he announces, “No more!” Suddenly, starlight and the cosmos are streaming through him, and the onetime thief is a half-moon, lighting the threshold to a jubilee.

Incongruous images like these startle us, wake us up from our habitual ways of thinking. When we allow poetry to transport us into its perplexing worlds, it becomes possible for something new to be born within us.

Contemplative Reading

In Word Weavers meetings, we borrow from the traditions of contemplative reading in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. In these ancient traditions, spiritual poems, stories, and texts serve as gateways into deeper self- and God-awareness.

In groups at the Center, we work specifically with poetry and lyrical prose. Since 2019, we’ve been walking through the sacred portals created by Rumi. In 2022, we added a new group, which focuses on the divine feminine in the Wisdom literature of the ancient Hebrews. Future groups may form around material like, The Tao Te Ching of ancient China, and the poetry of Christian nature mystics—both ancient and modern.

During these groups, we follow simple steps that turn reading into a spiritual practice. First, we read a poem, noting which phrases or metaphors capture our attention. Then, we read the poem a second time, noticing what thought, sensation, image, or memory stirs within us. Various responses can arise: We may feel inspired, baffled, sad, or angry, for example. Whatever appears, we receive these experiences respectfully, for they are guides and companions on our spiritual journey.

Next, we portray what we’re experiencing with art supplies, and/or spontaneous movements or sounds. If two phrases, metaphors, gestures, or sounds beckon, we sometimes entwine them in one creation. As we create, we consider making our expressive art an offering—a gift—to the divine life within us. This kind of offering is like one beloved giving to another, or a child presenting a loving parent with something of great value.

To conclude our expressive art, we practice letting words and images go, and rest for a while in mental silence. During this time, we also open to receive more deeply from our divine essence. Later, we often share our creative experiences with other group members.

During Word Weavers gatherings, then, we practice the basic skills of mystical introspection: Quieting the mind, exploring our inner world through our feeling sense, releasing whatever we discover to our divine core, and receiving from that holy presence.

Creating with Rumi

In addition to supplying verses for contemplation, Word Weavers gatherings provide biographical material about the authors that give context to their poems. In groups that focus on Rumi’s poetry, for example, we learn about his childhood as a refugee, and his experiences of friendship and loss as an adult. Knowing about Rumi-the-man helps us enter his poems more deeply. Below are descriptions of five Series (five groups, with three meetings each) that focus on Rumi’s verses.

Series One: A Caravan Without Despair

Poems: A Community of Spirit • The Guest House

• Our Caravan Bell and Come, Whoever You Are

Series Two: The World is a Meeting of Friends

Poems: On Being Woven • The Visions of Daquqi and Spring Murmur

• Love Came

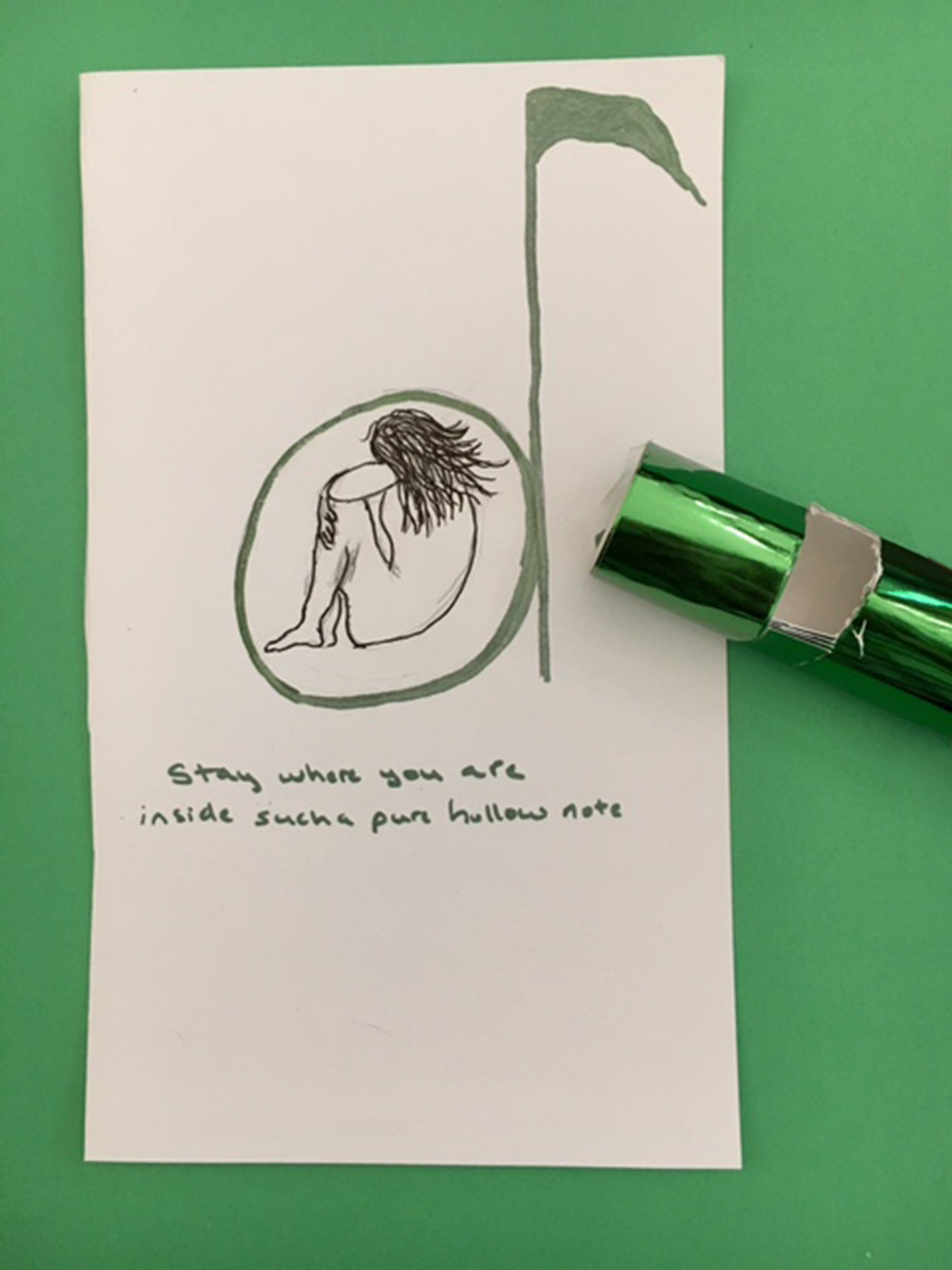

Series Three: The Wound is Where the Light Enters

Poems: The Reed Flute’s Song • A Thirsty Fish and

Dance When You’re Broken Open • What About my Eyes? and Silkworms

Series Four: Love Cannot be Said

Poems: Word Fog • Where Everything is Music • There is Some Kiss we Want

Series Five: I Feel Like the Ground

Poems: The Worm’s Waking • The Ground Cries Out • Say I am You

Heart Gallery

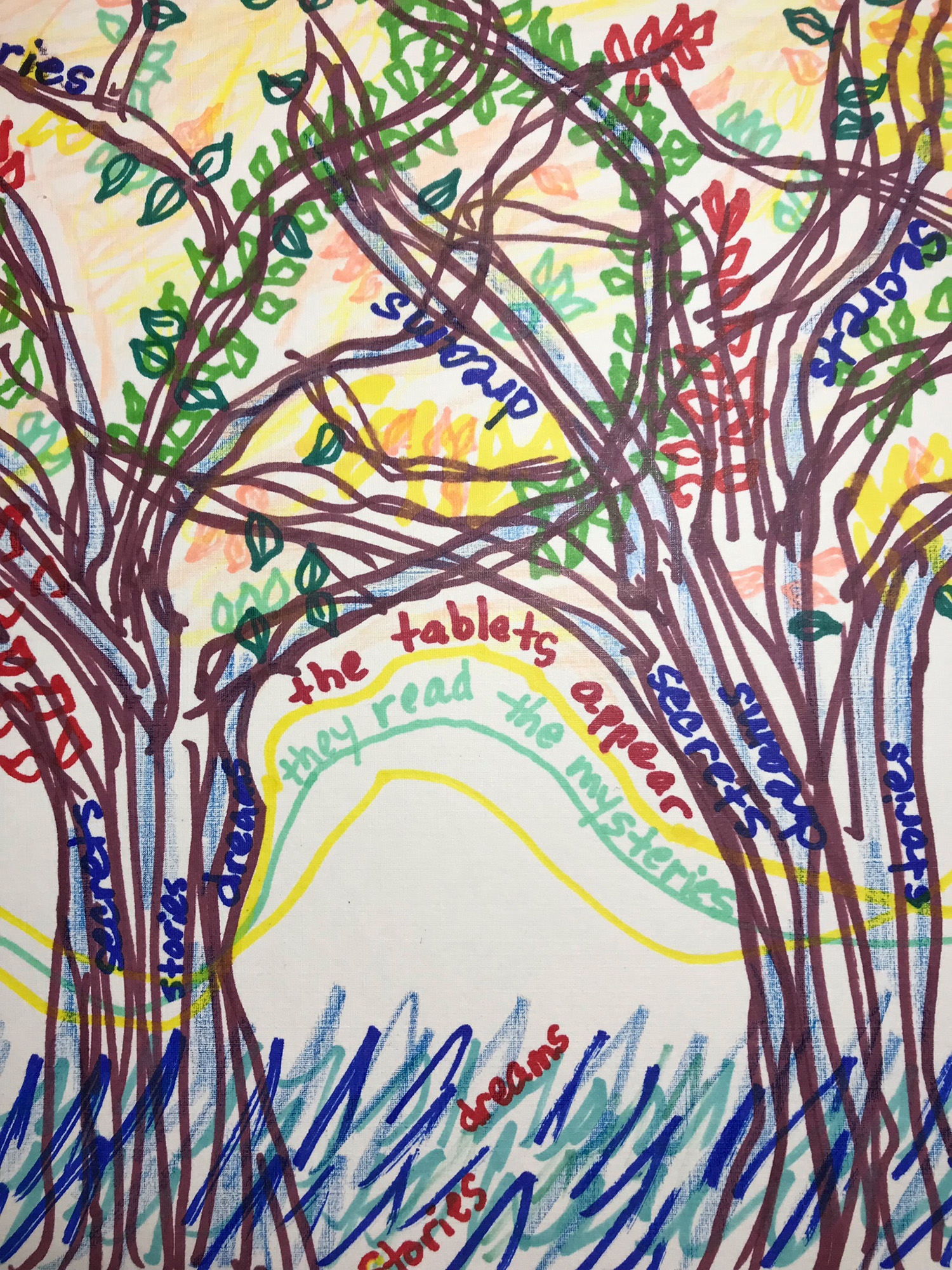

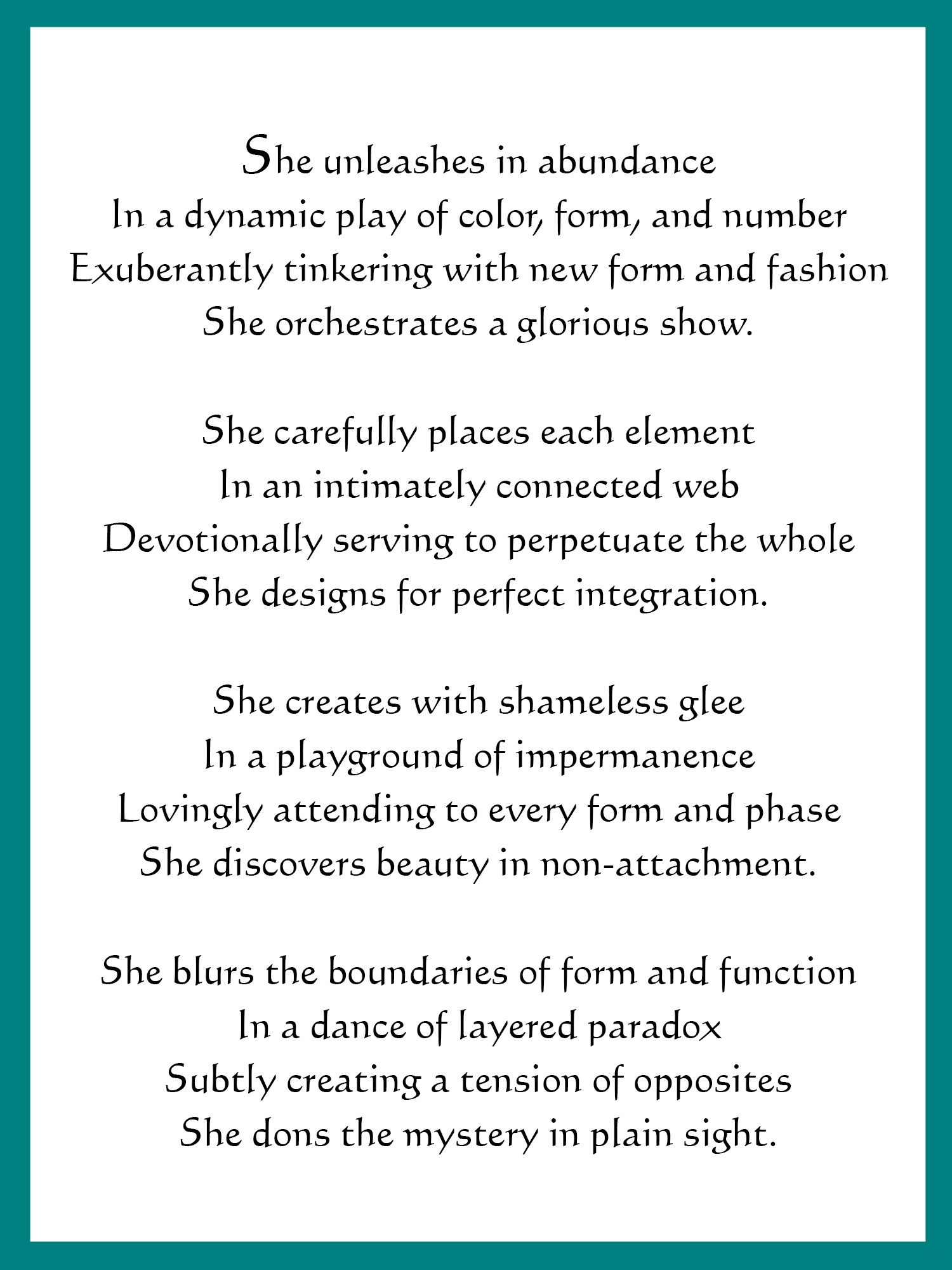

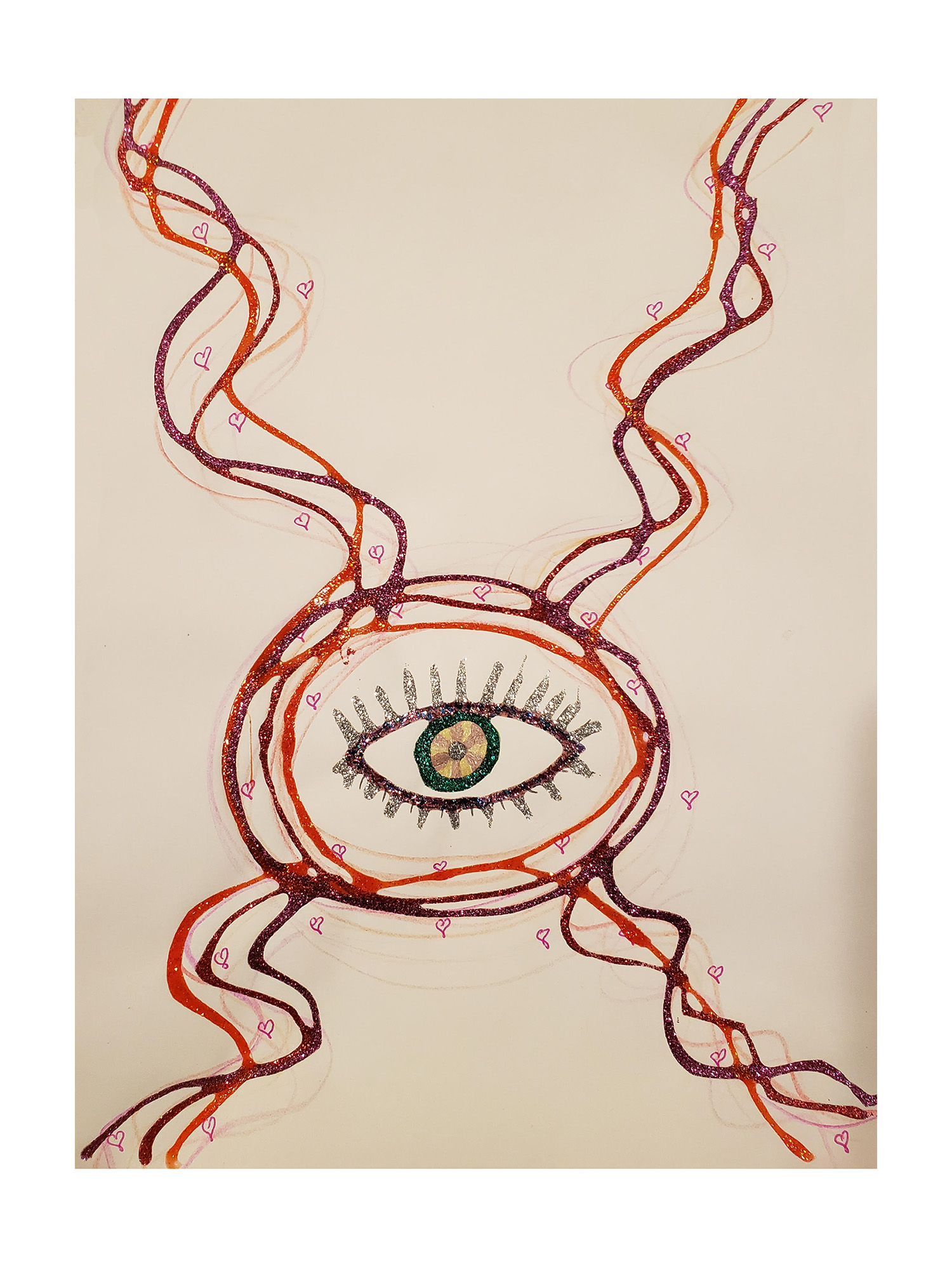

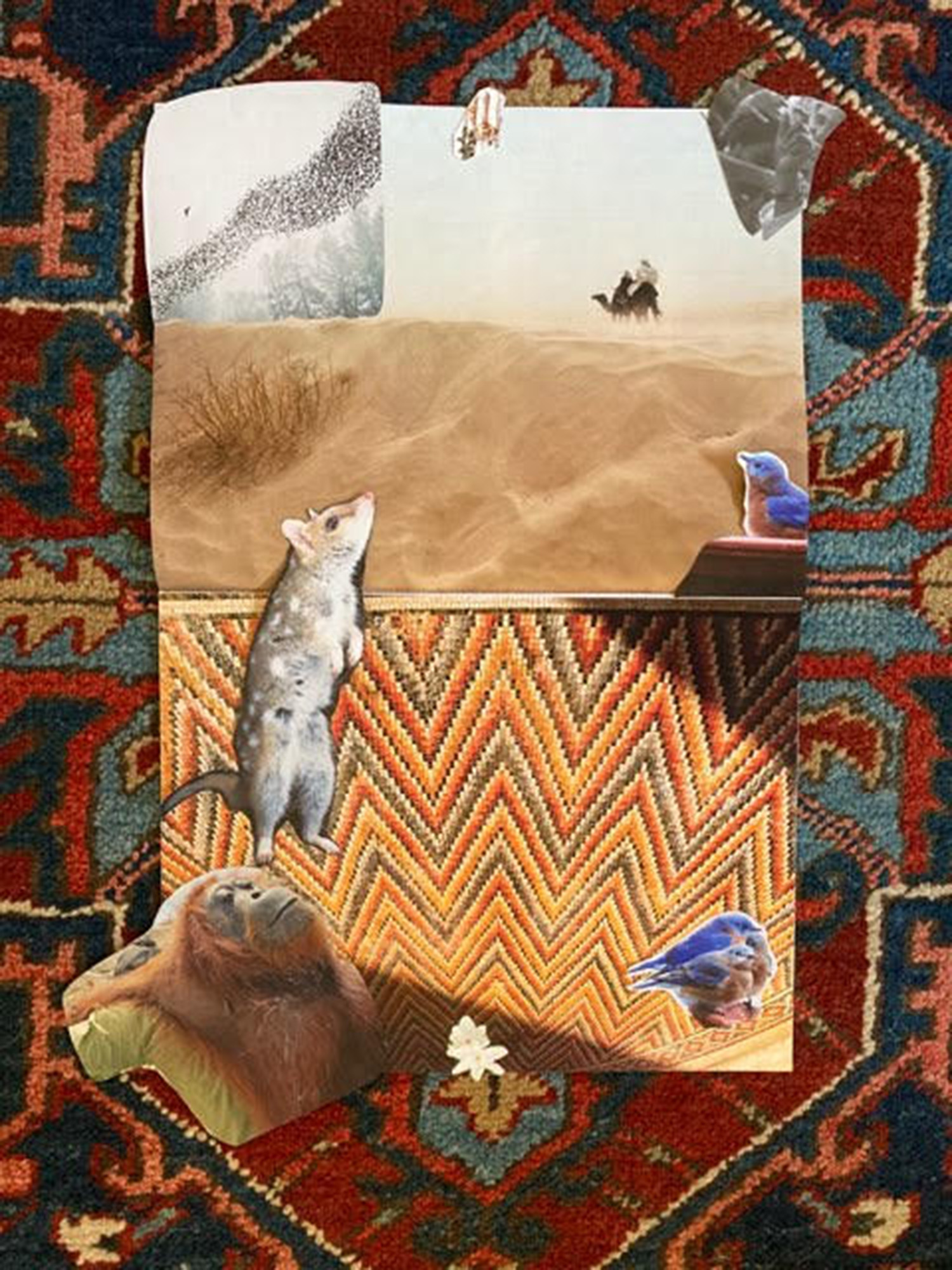

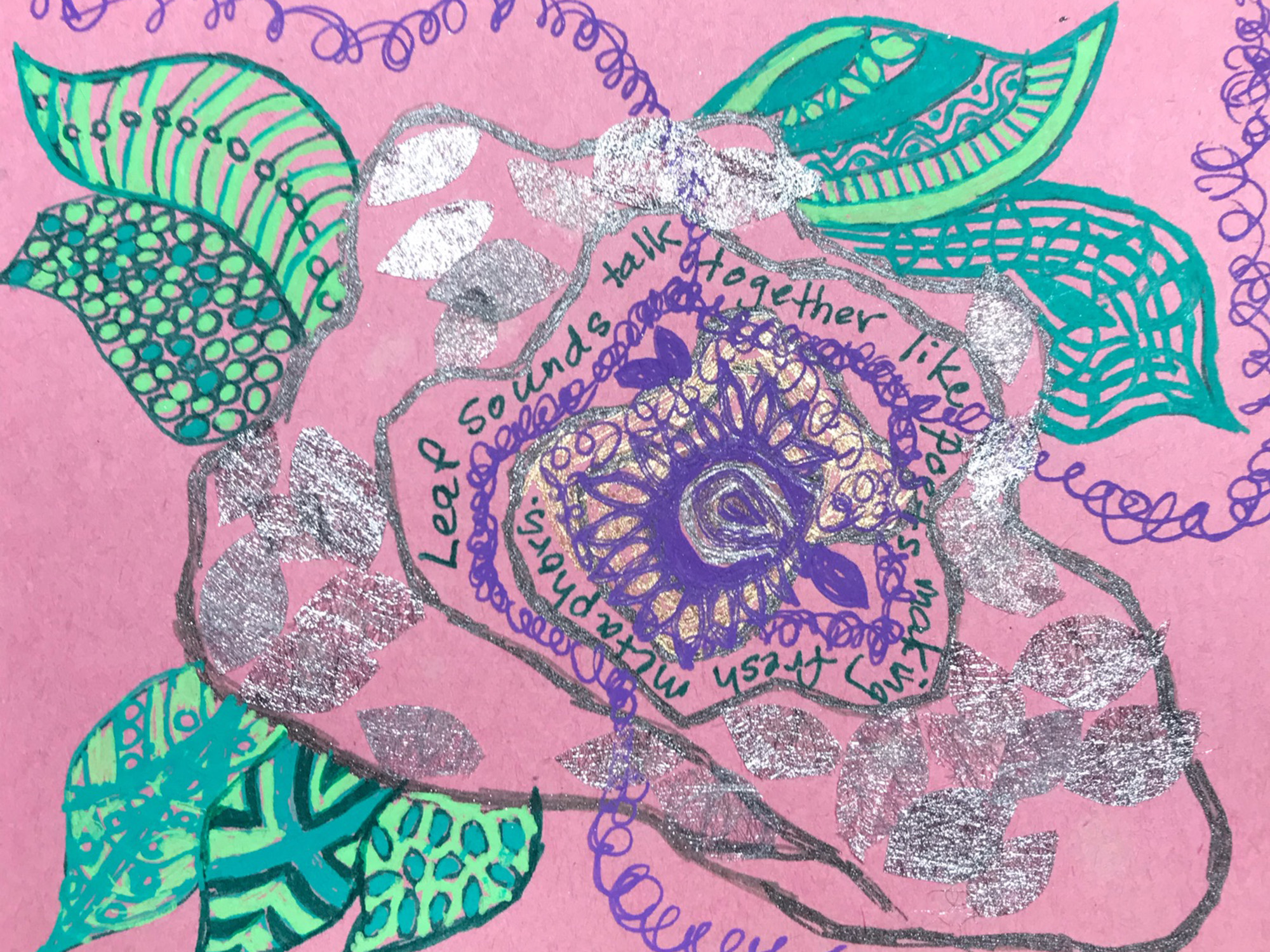

When Rumi’s words stir something important within them, Word Weavers participants portray a myriad of experiences. Below are several examples of their poem-inspired expressive art. I hope you’ll enjoy the many shapes, colors, themes, and materials that are displayed here. The Rumi quotes were translated by Coleman Barks.

As you contemplate these creations, please remember to engage your ability to feel. The power of spiritually oriented expressive art cannot be grasped through thought alone.

Please click on the artwork to see a larger version.

“Daring to Know”

“The dark thought, the shame, the malice, meet them

at the door…and invite them in.” Rumi

“This picture shows me as an Aware Child—an inner child involved in deep healing work. I’m exploring the hidden conflicts (depicted by crossed red lines on a black background) that characterized my original family.

“I began, wanting to depict myself in the process of acknowledging a ‘dark thought.’ I also wanted to create from below my conscious mind, so I closed my eyes, letting my dominant hand move unguided on the page. The crossed lines came spontaneously while my eyes remained closed.

“This child-self then appeared in my mind’s eye. She carried a turquoise scarf, reminiscent of flowing water—one of my favorite symbols for spiritual energy. I created this figure open-eyed, using both my dominant and subdominant hand.

“When I looked upon this art-piece after creating it, I realized that my precarious, ‘walking as if on a tight-rope,’ image accurately depicted my way of being in childhood. I was surprised and pleased to see how intrepid my healing child-self looked.”

“Bird Woman”

“Start walking….Your legs will get heavy

and tired. Then comes a moment of feeling

the wings you’ve grown lifting.”

Rumi

“Rumi says, ‘Let go, take flight!’ And why not?

My ego-shackle has weak links:

conflicting desires,

hurtful outcomes.

Suddenly,

I sense air moving—

rising, prompting, lifting.

I let this sacred current take me.

Its swift power loosens my ego-chain,

and I take flight in God.

Meanwhile,

the heavy weight hovers,

destination unknown.

My earth-shoes travel with me,

for I am a threshold creature,

made for land and air!”

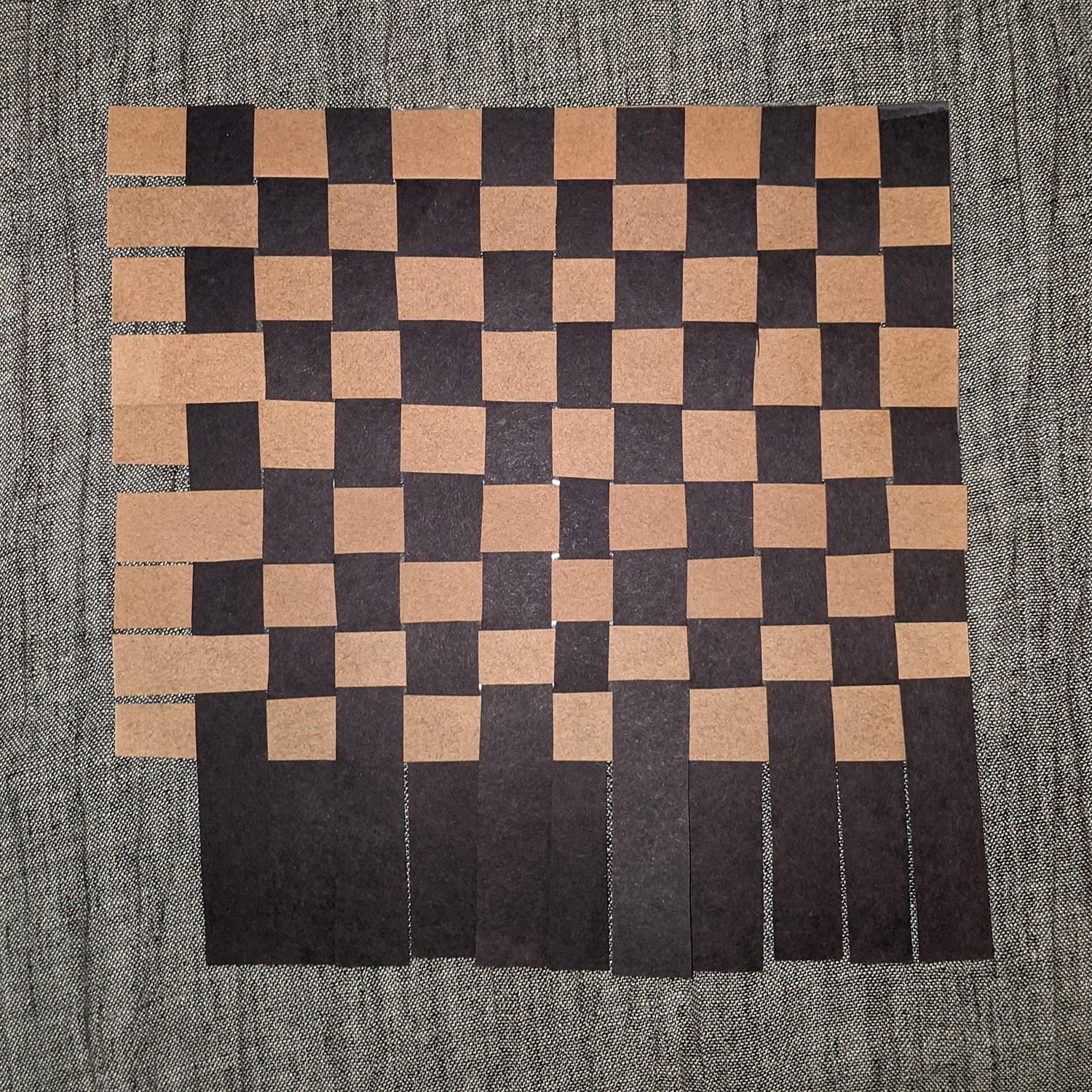

“Let it be Easy”

“When ink joins with a pen, then the blank paper

can say something. Rushes and reeds must be woven

to be useful as a mat. If they weren’t interlaced

the wind would blow them away.”

Rumi

“As I sat with Rumi’s poem, I was drawn to these three lines. My first thought was to ‘knit’ something with yarn for my expressive art, but then I felt an interior shift, and a desire to do something more simple. Staying with this inner awareness, the idea to weave with paper—and to surrender to ‘resting’—came to me. Soon after, these words arose within: ‘Don’t think, don’t look for metaphors in the poem…Just weave and breathe and rest….Let it be easy.’

“Using two different colors of construction paper, I wove a mat (like the one Rumi described in his poem), which reminded me of relationship, and of the qualities that emerge when two people join to create. They are individuals, yet together—equal, balanced, and free of domination.

“At the end, a question arose for me: ‘If my mat could talk, what would it say?’“

“Everything Pulses with Life”

“Narcissus looks love at jasmine. Iris jabbering….

Violet kneels, pretending….Hyacinth wags her head.” Rumi

Picture One: “Reading Rumi’s poem, ‘Spring Murmur,’ an image of vibrant colors (symbolizing flowers talking to each other) stirred within me. I began by painting watercolors in an abstract pattern, portraying ‘talking flowers.’ At the same time, I was distracted by a recent disagreement with my husband. While I created, my lingering anger ‘became’ watercolor paint, flowing as and through the field of flowers. Raw anger poured onto the paper with vivid strokes. It was as if my anger had taken form and could now be ‘seen and heard.’

“As I continued, I remembered the Friend, often spoken of in Rumi’s poetry. This memory brought a feeling of connection with the divine-as-Companion. Then, I sensed that the paper itself was my Friend: It was receiving paint, the way the Friend was receiving my anger. Sitting with this awareness, I realized I needed spiritual help with my turbulence. My art process was becoming an experience of surrender—a ‘prayer in action.’

Picture Two: “While I pondered my prayer, I sensed my anger being held. Then, in my mind’s eye, I saw hands emerge out of the colored paper. This artistic metaphor represented ‘hands from the Friend,’ which made me feel like my anger was being contained. The hands seemed alive, and flowing with energy. Since I used my own hands as a template for the cut-out hands, I was aware of my humanness and my divine nature at the same time—occupying the same space, together.

Picture Three: “My hands felt incomplete positioned separately, so I glued them together in a holding pose.

Picture Four: “I went to bed that night thinking I was done, but I woke up the next day with some difficult insights into my personal life (regarding relationships with aggressive authority figures). These insights led me to my fourth art-piece. Although I didn’t know what this image meant, I trusted my process and created what I saw in my mind’s eye.

“Finally, I recalled Rumi inviting us to listen to the presences inside poems—and to let them take us where they will. Without planning to, I’d followed Rumi’s guidance, allowing the presences inside his poem to take me where they would.”

“The Greening”

“Watch the fields, the flowers, the forest,

how they change in time….”

Rumi

“Sometimes while striving,

I forget my own being.

Then I dry out,

becoming weary,

sharp-edged, at cross-purposes.

Finally tired of strategies,

I await the dew of the morning.

This liquid gem comes quietly,

without blaring trumpets—

translucent and gentle,

transmitting light.

I receive its blessings, sense its touch:

a shimmer of wetness,

something cool and caressing.

My parched leaf-tongue

yearns for more, and more comes:

soaking my pores, giving me hope.

The greening has begun.”

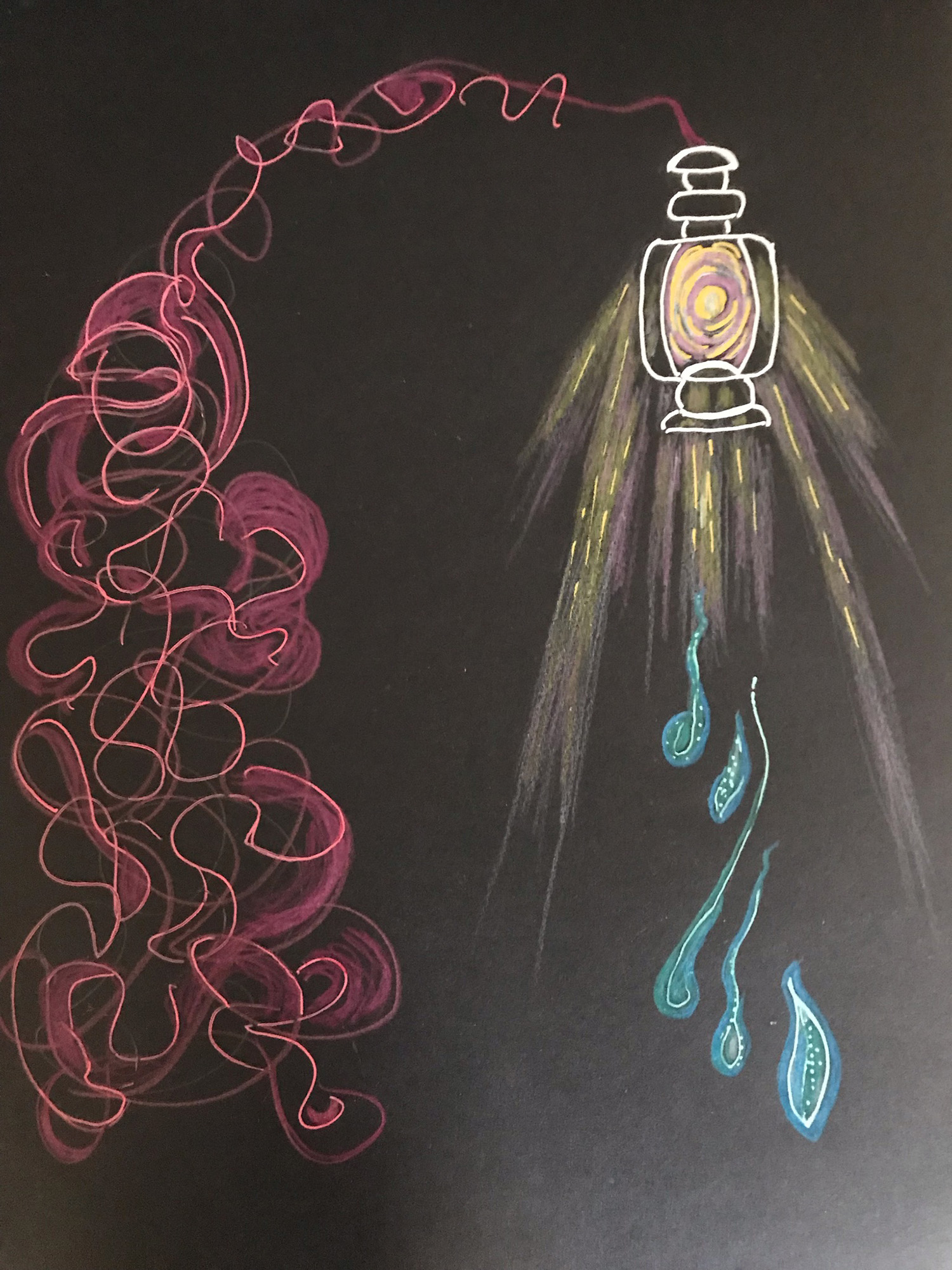

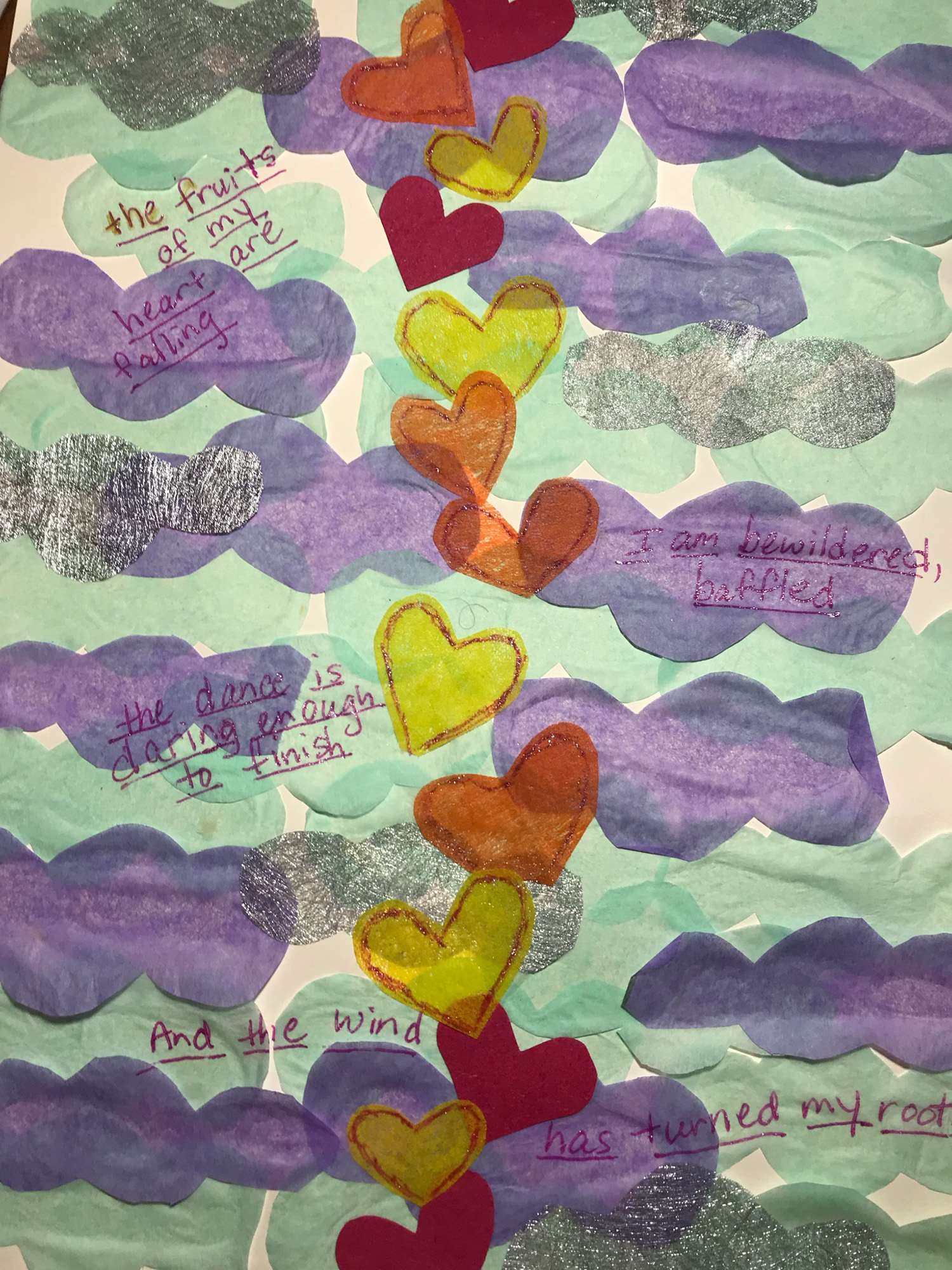

Glimpses of Word Weavers Art

Below are more examples of art inspired by spiritual poetry. To save space, these samples are presented without their accompanying narratives. With only the titles, the poetic quotes, and the art, you may glimpse the depth, tenderness, and playfulness that is possible when engaging in this spiritual exploration.